By Darcy Sprague

On Jan. 4th, a group of 29 health science and mass communication students journeyed into small communities in the Nicaraguan jungle where they met some of the locals and received some of the warmest welcomes of their lives.

The people who gave these welcomes were mostly women who were home with their children. Smoke billowed as they cooked or burned trash, and soapy water from washing dishes and clothes ran in the streets.

A 2015 report from the United States Agency for International Development states, “we know that women are vulnerable to extreme poverty because they face greater burdens of unpaid work… and are more likely to be forced into early marriage —all factors that reduce their ability to participate fully in the economy and to reap the benefits of growth.”

During the 2017 College of Health Sciences study abroad trip to Nicaragua, the team met many different women. Some were living in extreme poverty and some spoke candidly about their or their parent’s struggle for a better life.

The group that conducted house visits in Los Rio or Butter as it was referred to by the students, saw few men that first day. Many of the men were out working. Most of the men who were home were ill, leaving their wives to both earn money and do the house chores.

In Nicaragua, low income women are 12 percent less likely to work than men. Middle class women are 30 percent less likely, according to the World Bank Gender Portal.

Petronila Melendez, a 90-year-old woman who visited the Butter clinic, had 14 children and outlived nine of them. She still cooks, cleans and occasionally works in the fields to earn money.

She had three husbands in her lifetime. Two of them died and one left her. She lives with her son who does not currently work and does not help support her.

“I had a lot of children so I worked all the time,” Melendez said through a translator. “I wasn’t a very lucky lady.”

Melendez carried heavy baskets of fruit on her head from her village to the local market for 40 years.

She had her first child at the age of 14 after being raped. She married at 22.

“Your son will probably die before you do,” the doctor who saw her joked. “Is your house older than you or are you older than the house?”

Melendez admitted she had little education. She lived her entire life in the same area.

In contrast, Massiel Acetune Vilchez, the 33-year-old International Learning Service team coordinator who assisted the group on the ground, lives in a four-bedroom house. She does not work in a labor intensive position. She has no children and is not yet married.

She said this is because she wanted to get her education and career in order before she settled down.

Vilchez’s mother grew up in a village similar to Melendez, but she had an “I deserve better” attitude, Vilchez said.

Her mother moved to the city and graduated from one of the free public universities. She met and married her husband, but continued to work. Her father lost his job so her mother moved to Miami to get a job. She sent money back so that Vilchez and her siblings could have a good life and education.

Vilchez said her parents always expected her to be in the top of her class. She received a scholarship and was able to attend a private university.

“My mom and dad raised me to be independent,” Vilchez said.

Vilchez said she has a different view of gender roles than many of the women who came through the clinic.

“I believe in 50/50,” she said. “I can cook, but so can a man.”

She added that her older brother cooks and cleans for himself.

“It’s not about gender,” she said. “It’s about how you can be independent in every way. I want (my daughter) to be a powerful woman. I want them to fight for their dreams and for them to want to accomplish more.”

Olga Fonseca, 69, was another of the local women who came into the clinic and who had a life similar to Melendez’s.

Fonseca had 13 pregnancies and raised eight children. Now a widower, Fonseca lives with her 41-year-old son and supports herself by baking desserts in a wood hole in her house similar to a pizza oven.

Every morning she wakes up at 3 a.m. to make coffee and sweep the house. She prepares the desserts and cooks bean and rice for her and her son. She cooks until lunch, then begins cleaning again. She does not rest until after dinner when she reads her Bible. She goes to sleep at 11, resting for four hours before starting again.

Fonseca was never able to have an education. She has struggled for as long as she could remember just to make ends meet.

Fonseca lives off of 60 cordova a day, which is about $2 USD. Her son does not work or help with expenses.

Struggling is not unique to the women of the village.

According to the World Bank, in 2008—the latest complete data available—roughly 42 percent of Nicaraguans live in poverty. Sixty-three percent of people living in rural areas are poor while only 27 percent of those living in urban areas fell below the poverty line.

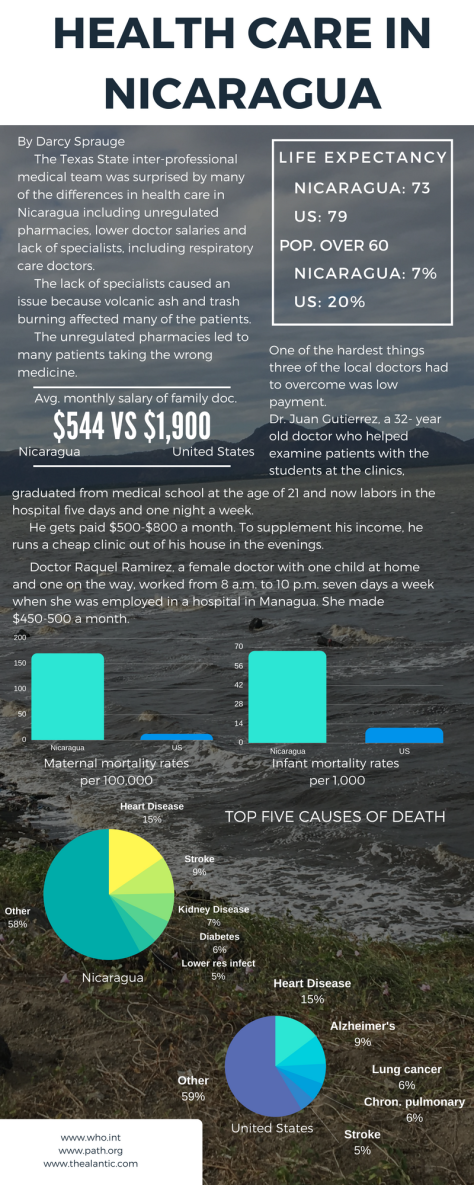

Raquel Ramirez worked as a translator for the group, but most days she is a doctor. Currently pregnant, she is having a hard time finding work.

In her profession she was working from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. six to seven days a week.

“We make due,” she said. “I like what I do, but sometimes I need family time.”

Ramirez earned $450-$500 a month as a doctor. The poverty line in 2005 was $413.53, according to the World Bank. Ramirez, a doctor, one of the highest paid professions in the United States, barely earns enough money to be above the poverty line.

Women are making some headway in the country, however. Women are eight percent more likely to attend secondary school than men, and female children are four percent more literate than males.

“It’s not about opportunity, it’s about education,” Vilchez said. “Some f these families don’t know about thing else besides their village, they do not try to move on.”